Room to Breathe Program Guidelines

Case Study

Room to Breathe (RtB) is a Northern Territory Government program designed to address the negative effects of overcrowding in remote Aboriginal communities.

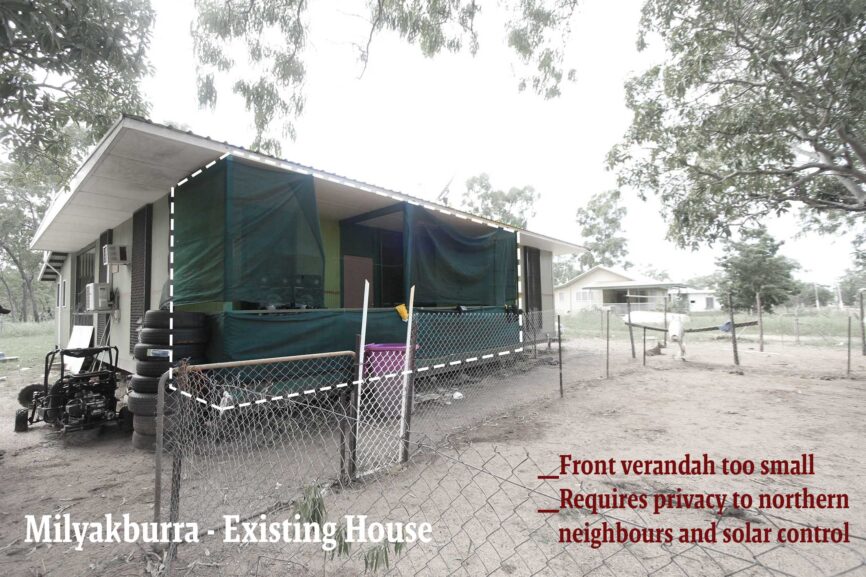

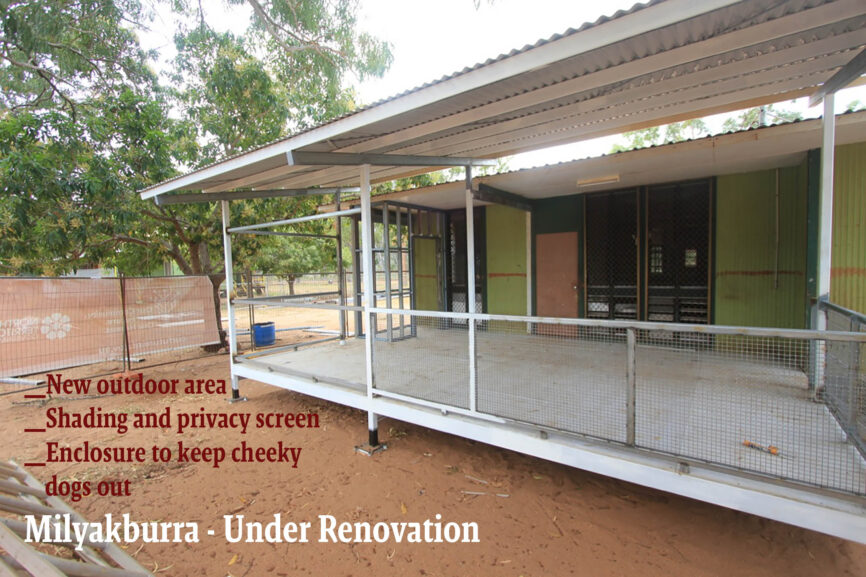

RtB is essentially an alterations and additions program being rolled out across 73 communities over the next 10 years in the Northern Territory.

It was devised in response to repeated recommendations to shift the focus from building new houses to improving existing housing stock.

The vast quantum of research and knowledge in this space suggests that crowding stress often comes from a sense of loss of control over one’s household.

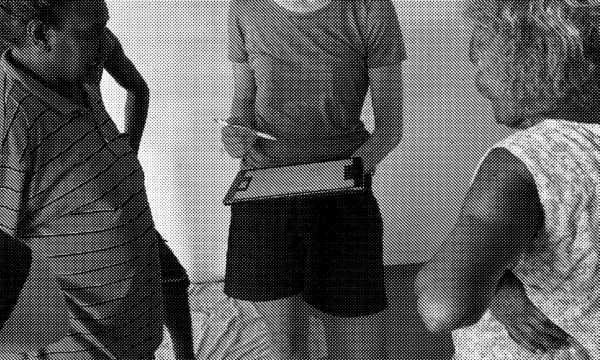

Consultation with members of the Gapuwiyak Housing Reference Group in regards to the rollout of RtB in their community.

What did we do?

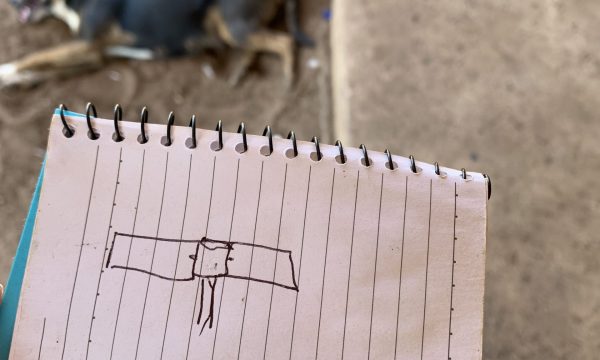

Local Decision Making (LDM) is a critical foundation for the RTB program rollout. The RTB methodology is designed to empower local decision making and enable the co-design of alterations/additions and improvements to housing through a rigorous community engagement and design process.

This approach is unique in state subsidised housing programs. TF.A created Guidelines to provide a framework for the implementation of this rigorous, complex and bespoke program.

Foremostly, the Program Guidelines are there to guide the design, procurement and construction of dwelling additions and alterations, which are habitable, safe and secure, providing a solid foundation for people to raise healthy families, undertake work and social activities, and engage with their community.

Creating the Guidelines

Our intent in creating the guidelines was to provide people working on the program with a nuanced and holistic method of assessing levels of overcrowding.

We proposed an evidenced-based approach, founded on the cultural qualities of Aboriginal people, and with the following design objectives:

Appropriateness / Cultural Appropriateness / Accessibility / Healthy, Safe & Secure / Economically Sustainable / Built Properly / Site Responsiveness

We know through research and observation that one of the key pressure points in a home is the bathroom. Crowding stress occurs when you haven’t got the right ratio of showers and toilets to the number of occupants, or bathrooms located in the right places for cultural practices. To address this, we incorporated an assessment of a household’s health hardware as a key component to the process.

We suggested a more consistent approach to consultation and engagement and provided a method for ensuring that tenants are involved in the design process.

We developed a list of questions for consultants to ask in community that would help them to work out who’s happy, who’s not, and most importantly, why?

We defined the parameters of the program, detailing what improvements can be offered to a tenant and what sits outside the scope.

The impact of these changes will be seen in coming years. What we know so far is this:

It’s more cost effective to renovate than to build new houses.

An individual approach has the capacity to respond to cultural practices, proposing appropriate spatial arrangements.

People appreciate their houses more when they’ve been involved in the design process.

People feel empowered and quality of life is improved when people have made decisions for themselves.